A walk through tea

Gill Juleff

Anyone who has travelled through the tea plantations of the central highlands of Sri Lanka will have a favourite place, or view, or experience that lodges in their mind that, when triggered, evokes a tumble of sensory memories – a smell, the breeze, a breath-taking view and the comfort of a tamed landscape. For me, that place is Haputale and the long walk east to Dambatenne, the estate made famous by Sir Thomas Lipton and Lipton’s Tea. I first visited Haputale in 1984 as a backpacking tourist, and have returned there, whenever an opportunity can be engineered, ever since.

Haputale is essentially a crossroads town but a crossroads between very different regions. The town occupies a gap in the southern escarpment of the highlands. To the south, the land falls away dramatically and the road winds down hairpin bends through the foothills to skirt the bottom of the escarpment, eventually reaching Ratnapura and the level plains into Colombo. Looking more directly westwards in the distance is the profile of World’s End and Horton Plains, among the highest points on the island. On a good day it is possible to see a vast sweep across the low hills down to the wide plains that stretch to the coast. On a very good day it is just possible to see the coast, 75 miles away. And on a bad day, when blankets of fog rise up from below, you won’t see your outstretched hand. Turn through 180° and the view is of the gentle rolling hills of the Uva basin with its patchwork of plantation settlements, tea factories, bungalows connected by winding roads and lanes and all set in a carpet of green tea.

The crossroads of Haputale is in fact a crossing of road and rail. The Kandy-Badulla railway follows the ridge of the escarpment and anyone travelling has the choice of looking south to glimpse the precipitous drop of the escarpment or north into the tranquillity of the Uva basin. The all-important station is in the centre of the small town and the line crosses the main street, imposing regular level crossing closures. Across the line is the marketplace and bus station encircled by small shops to one side and a raised headland overlooking both market and railway line. In this strategic position sits St. Andrew’s Anglican Church. The church dates from 1869, during the early years of tea development in the Uva basin, and was a social focus for the growing local planter community. Externally it is modest, with a corrugated iron roof and a well-maintained and populated graveyard. The headstones make interesting and sometimes poignant reading. Included among a number of well known planters are also children of planter families and those who lost their lives in plantation accidents.

The interior of the church, with its stained glass windows imported from Scotland and plethora of memorial plaques, is equally well-maintained by a lively congregation drawn primarily from the plantation labour community. On one of my earliest visits to Haputale, I attended a Christmas morning service with a small group of European friends. We occupied pews on the left side of the nave while most of the congregation sat on the right side, close to the pulpit. On the singing of carols a battle commenced between the two sides with simultaneous renditions in Tamil and English, and the vicar valiantly alternating between the two on each verse. It was an ice-breaker and resulted in chatter and laughter.

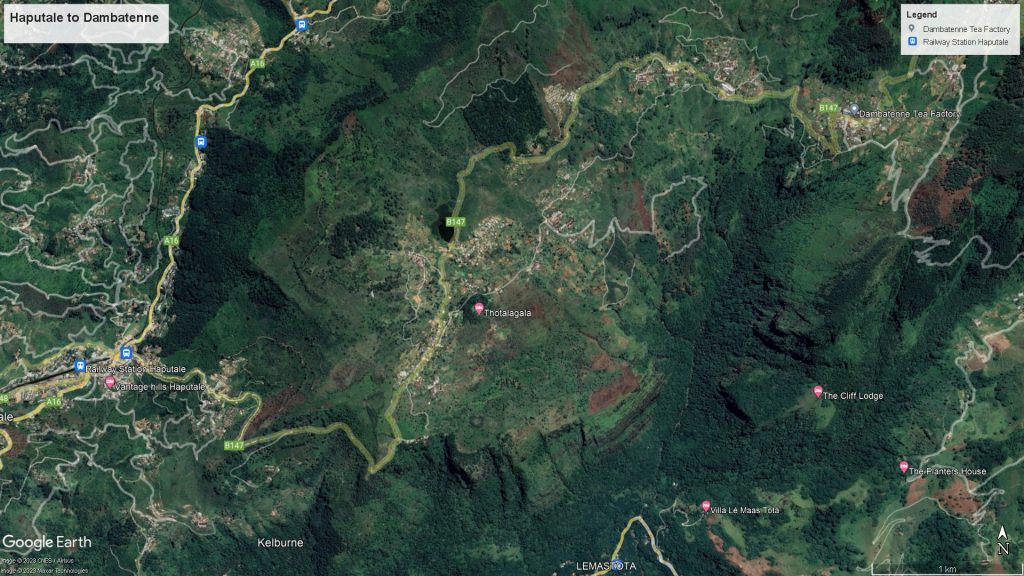

From the eastern side of the marketplace, the road to Dambatenne heads out of town. It leads only to estates, culminating at Dambatenne, so all the traffic relates in some way to the plantations. Its route follows the contours of the escarpment and climbing the first slope gives views back across the town and westwards towards World’s End. Then, turning the first hairpin bend, the view casts eastwards into the small amphitheatre of Kelburne estate. Here the plantation becomes intimate. Tea grows tight to either side of the road and extends up and downslope. You begin to look closely at the bushes themselves, seeing their twisted, almost bonsaied, roots and branches. You start to discern the system of harvesting through the colour of the bushes, with the dark green showing areas recently plucked and the acres of shimmering pale silvery-green of new shoots ready for plucking. The warm air holds a familiar scent you recognise as tea (when tea was brewed from loose leaf rather than in sterile little bags). At this level you see, dotted across the fields, small groups of tea-pickers, mostly women, barging their way waist or chest deep through the dense bushes. As well as their collecting sacks slung from their foreheads, each has a long cane that they place on top of the tea to guide and orientate their work. There will be chatter and banter across the bushes but their progress is methodical and sure-footed. The density of the planting means you can’t see your feet and the ground is rocky and networked with roots, as well as being home to snakes and scorpions, bites are a constant danger.

Back when I first discovered it was possible to book to stay in the planter’s bungalow, Kelburne was, in the era of the state tea monopoly, a relatively rare privately-owned small plantation. The hub of the estate still had a small tea factory, no longer processing tea but acting as the estate collection and weighing station. Inside the factory, although empty of its machinery, the wooden stairs and floors of the three storeys filled the space with the warm aroma of tea. The full-time superintendent lived in a bungalow close by the factory and the modest plantation owner’s bungalow, a little way away, occupied a prime position for views down and along the escarpment. In the pre-digital age the bungalow was lined with National Geographic and Reader’s Digest magazines to peruse on long evenings by the fireside. Over the years and many visits, as small estates have been subsumed, post-privatisation, into larger plantation corporations, Kelburne has changed. The factory has been demolished and the tea is now collected from the roadside and taken to bigger factories. All the bungalows have been upgraded and are now marketed as exclusive holiday ‘cottages’ that I would recommend to any visitor, despite my nostalgia for the simplicity of the 1980s.

Continuing along the Dambatenne road and turning another hairpin bend brings you to a much larger amphitheatre that opens up for several miles. Dambatenne factory and central buildings are visible at the farthest end of the amphitheatre, and in between are carpets of tea interspersed with steep slopes and crags forming the edge of the escarpment. Tea clings to the slopes as far as possible, which means as far as humanly possible to pluck the tea. The road is deceptive. Although your destination is clearly visible it doesn’t seem to get any closer no matter how far you’ve walked, but, thankfully, the route is true to the contour and comfortably level. While the distant views in all directions are breath-taking there is also plenty to see at close quarters. When I first walked this road it was quiet, with the only traffic being plantation vehicles and the occasional highly-dilapidated public bus. Now, since the end of nationalised plantations and improvements in estate worker’s rights and conditions, the road is busier, with small trucks carrying vegetables, grown in plantation worker plots, to the market in town for distribution further afield, local three-wheeled (tuk-tuk) taxis and very occasionally a tourist bus or car. Compared with more than four decades ago when the people you met walking on the road were timid, there is now a buzz of activity and an air of increasing prosperity.

Along the way there is more than one estate but to the untrained eye it is difficult to distinguish where one ends and another begins. The roadside is dotted with signs indicating the estate division and field numbers. It is a mysterious but intriguing coding system. Thotalagala is the first plantation along the way and its overriding feature today is its bungalow. Tucked out of site below the road, Thotalagala was the home of Sir Thomas Lipton in the 1890s when he commanded all the tea as far as the eye could see. Now it is a showpiece of the lifestyle of the elite British estate owners. Not that just anyone can wander around its well-watered lawns and cool verandahs. Dipping into planter’s luxury is for those wealthy enough to hire a suite in the bungalow for a short stay, or a nosey foreign visitor ostensibly curious as to whether it might suit their future holiday plans.

Pitaratmalie is the next name encountered and here you pass a rare remaining patch of natural forest that is now carefully conserved. How it survived the original clearing of the land I don’t know but the drop in temperature as you walk through its shadow is beautifully noticeable, a reminder of the climate impact that must have resulted from the wholesale clearance of the natural forest.

Across the landscape are small clusters of buildings that form the living spaces for those who work on the plantations. In the past these were predominately dismal ‘lines’ of uniform one- and two-room homes often with external cooking and washing facilities. Still these can be seen and are in use but over time they are being gradually replaced by larger houses and more space made available for garden plots, so that the settlements are beginning to look more human and relaxed. That’s the appearance to an external observer on the ground or a devotee of Google Earth historical imagery. To understand really what life is like here you would need to be invited in by the community, which is more than possible for those who want to learn. Larger settlement clusters also have communal buildings such as infant and pre-schools, shops, health centres and places of worship.

Walking further eastwards towards the business end of Dambatenne estate and a small promontory protruding from the amphitheatre comes into view. It is distinctive for its appearance of order and its lush vegetation. Here the tea looks most manicured and the trackways winding through the tea are uniform and well-maintained. This is the showpiece centre of the estate. Hiding among mature trees are glimpses of the green roof and white walls of the large manager’s bungalow. Sitting above the promontory is the imposing Dambatenne factory and as you finally take the last bend the four-storeyed silver and green of the corrugated-iron and glass structure looms in front of you.

There are regular tours of the factory so you should be lucky to get inside to breath in the all-pervasive aroma of tea and feel the gentle thrum of fans and rolling machinery. The process of turning fresh green tea leaves brought in from the surrounding fields into black tea ready for consumption is relatively straightforward and has remained largely unchanged since the late 19th century. Electricity has replaced huge quantities of felled wood to fuel the furnaces that drive the fans that dry and roast the leaves but the conveyor belts and hoppers that move the tea through the factory, from drying to roasting and rolling, cutting, shifting and grading, are as they have always been. From the top floor, the leaves move in orderly and timely fashion down through the factory, recorded carefully through each stage, to be bagged and labelled on the ground floor ready to be loaded on lorries headed for Colombo and shipped on into global tea markets.

My walk ends outside the factory and I’m reasonably assured that it won’t be many minutes before a convenient bus or three-wheeler appears that can take me and my weary legs back the same way toHaputale and a nice cup of the best BOP Ceylon Tea. You, however, might want to make the further steep climb up through the plantation to the well-signposted Lipton’s Seat viewpoint. Up there you will find Sir Thomas reclining in satisfaction, gazing out upon his great works, and an information plaque that tells you of his legendary picnics in this place, regaling his guests with his visions for ‘Ceylon Tea’. Personally, I don’t want to give oxygen to this valorising narrative of the of the heroic planter. It was the work of many generations of disenfranchised and badly treated labourers that created this landscape and the wealth taken from it. And in creating it, another landscape was destroyed, one which we may not have been able to visit and walk through with the same ease but would have benefitted our planet’s health far better than tea. Also, I don’t need to use up my own oxygen scrambling up to this place when the views from the road I’ve walked have been sufficiently dramatic and the glimpses I’ve had of life along the way tell me far more about the plantations now and in the past than the story of Sir Thomas Lipton.