Gill Juleff

It is the Inland Countrey therefore I chiefly intend to write of, which is yet an hidden Land even to the Dutch themselves that inhabit upon the island. … This Kingdon of Conde Uda [Kandy] is strongly fortified by Nature. For which way soever you enter into it, you must ascend vast and high mountains … The Hills are covered with Wood and great Rocks, so that it is scarce possible to get up any where’ (Knox 1681)

The central highlands of Sri Lanka were, until the arrival of the British, inhospitable and impenetrable to the outsider but providing a secure and resilient home for the Kingdom of Kandy and its inhabitants. Environments across the highlands depended on aspect, with the southwest side of the hills receiving maximum rainfall, and elevation, and ranged between tropical rain forest, montane and sub-montane forest and patana grasslands.

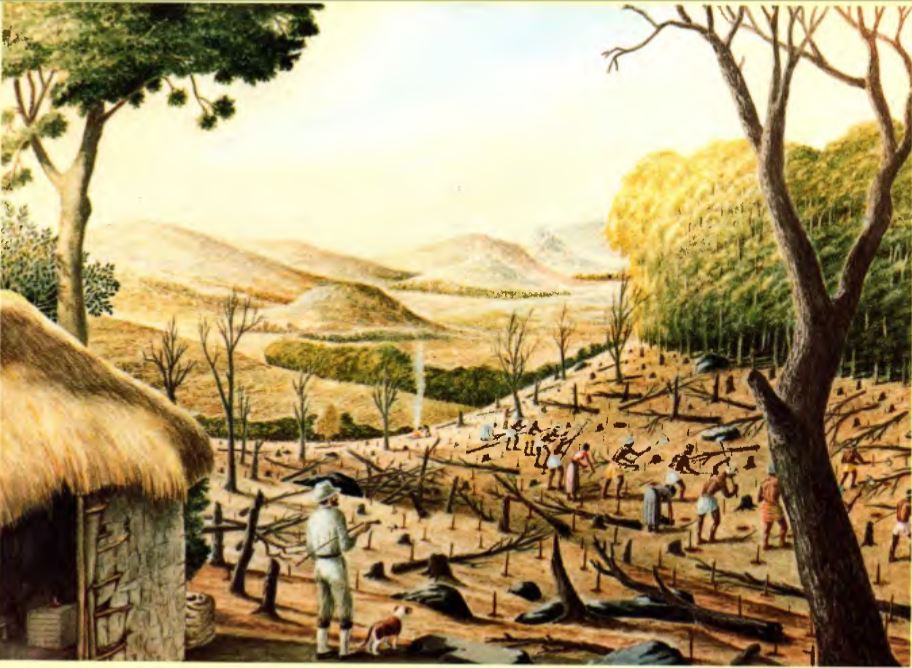

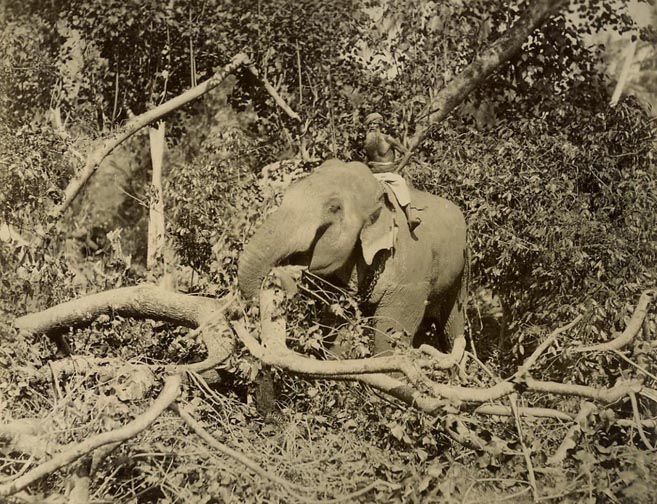

To create the space to plant coffee and tea, land had to be cleared to bare earth. The wholesale clearance of mature indigenous forest and grassland across the highlands began in the 1830s and continued relentlessly over a hundred more years. The ferocity and determination of the ecological destruction was akin to that witnessed today in Brazil, the only difference being that in Sri Lanka it was achieved by human hand rather than machine, with only the assistance of axe and elephant. For the British planters who orchestrated the devastation it was the work of power and control, a display of machismo and superiority, bringing the wilderness into civilisation. For the land itself it was a physical brutality that left scars that are still unhealed today. For the creatures that lived on the land it was a mass expulsion leading to near-extinction levels of loss.

‘I was still in my teens when I landed … I lived in the Singhalese village while the felling of trees went on by low country Sinhalese contractors … sometimes the thunder and lightning was playing on my head with terrific grandeur … I know of no more awe inspiring sight than a thousand acres on fire … appalling cries of birds, rilawas [macaque monkey] and elk …’ (Richard Wade Jenkins[1] in Breckenridge 2001, 42)

Major Thomas Skinner[2] (Surveyor-General, road builder, and explorer) on ascending Adam’s Peak (sacred and fourth highest peak at 2,243m) expounded his vision for Ceylon …

‘Clearing this trackless wilderness of 200,000 to 300,000 acres of forest, to be the means of removing 20,000 half-famished creatures from South India to such relative paradise and also benefit our Sinhalese people who are compelled to hide in places scarcely accessible …’ (Breckenridge 2001, 69)

A.M. Ferguson who sponsored and wrote prolifically on coffee, and pioneered a Handbook and Directory on the plantations. In his ‘Song of Uva’ he mused …

‘Ye hills and vales from Badulla to Haputhale’s crown

The coffee shrub is springing, the forest going down …’ (Breckenridge 2001, 46)

Clearing the land

The first task was the felling of the forest, usually in 50 to 100 acre blocks. The fallen trees would be left to dry out in the hot sun for two months and then the whole clearing would be ‘fired’. Felling trees for land clearance was one of very few areas of plantation work carried out by local Kandyan villagers, acting as contractors. Almost universally the Kandyans spurned the opportunity to earn wages under the gaze of the planter and his superintendents. It ran alien to the subsistence but well-provided comfort of their forest garden plots and paddy lands. However, their expertise with the axe and their knowledge of the vegetation and terrain meant they held the monopoly in felling the jungle. They had a particular technique for felling steeply sloping land, as described by John Capper, a planter with journalistic experience.

To me it was a pretty, as well as a novel sight, to watch the felling work in progress. Two axemen to small trees, three and sometimes four to larger ones, their little bright tools flung far back over their shoulders with a sharp flourish, and then with a ‘whirr’ dug into the heart of the tree with such exactitude and in such excellent time, that the scores of axes flying about me seemed impelled by some mechanical contrivance, sounding but as one or two instruments. I observed that in no instance were the trees cut through, but each one was left with just sufficient of the stem to keep it upright. In half an hour the signal was made to halt by blowing a conch shell; obeying the order of the superintendent, I hastened up the hill as fast as my legs would convey me, over rocks and streams, halting at the top, as I saw the whole part do. They were ranged in order, axes in hand on the upper side of the topmost row of cut trees. I got out of their way watching anxiously every moment. All being ready, the manager sounded the conch sharply, two score voices raised a shout that made me start again, forty bright axes gleamed high in the air, then sank deeply into as many trees, which at once yield to the sharp steel, groaned heavily, waved their huge branches to and fro, like drowning giants, then toppled over, and fell with a stunning crash upon the trees below them. These having been cut through previously offered no resistance, but followed the example of their upper neighbours, and fell booming on those underneath.

Within ten years of creating the first plantation, nearly 4000 acres around Kandy had been felled. No forest was safe from the axe and no mountainside without its pall of blue smoke rising from new clearings. In the case of coffee, the young bushes could be planted around the burnt remains of the forest, which helped to some small extent to allow the soil to stabilise and the earth to recover. With tea, the smaller bushes were planted closer together and on steeper slopes so the earth had to be cleaned bare before planting. Soil erosion from the steep slopes was a constant problem and new cross terraces and retaining walls were introduced, all constructed manually by immigrant labour. The climate of the highlands, with seasons of strong winds and high rainfall associated with the monsoons, increased the loss of denuded soils. Soil fertility was naturally low but served the undisturbed and diverse forest and grassland species well. The monocultures of coffee and tea, however, depleted the soils further and there were endeavours, led by officers and experts employed at the Peradeniya and Hakgala botanical gardens, to introduce materials and regimes for fertilisation. Schemes were promoted for planting introduced trees, including South American Poinsettia, within the tea to provide shade and wind breaks. Despite the unchecked momentum of forest destruction during the 19th century there was some reflection within the botanical community on the ecological impact of the changes being wrought (Webb, 2002, 103-6). There were comments on the changing climate of the hills, with opinion being this was largely for the better. There was concern that stream courses were drying up and the British administration brought in measures, largely ineffective, to create protective reserves along stream banks. Overall, however, these concerns provided little braking to the onslaught. By the first quarter of the 20th century, the hills had become what we see today, a patchwork of plantations interspersed with small, isolated islands of original forest and grasslands clinging to the steepest and most inaccessible slopes.

Clearing the animals

The land was stolen from the animals

The animals were stolen from the land

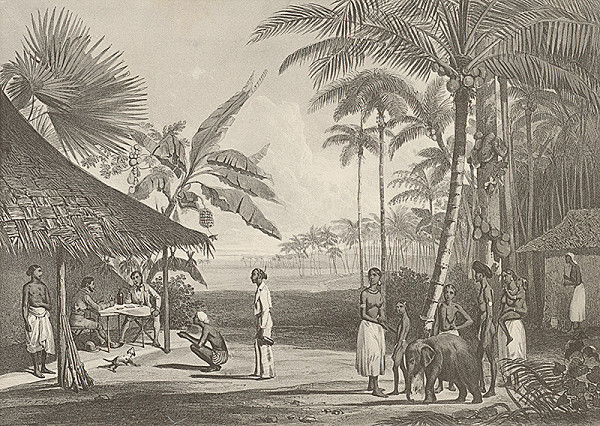

Most descriptions of the highlands before the creation of the plantations claim that, other than the mid and low hills around Kandy, they were uninhabited, justifying their wholesale acquisition for planting. But they were inhabited – by populations of animals. Where animals and humans came together in and around the Kandyan villages, the two populations co-existed with limited infringement of each other’s liberties and due reverence for each other’s place in the world.

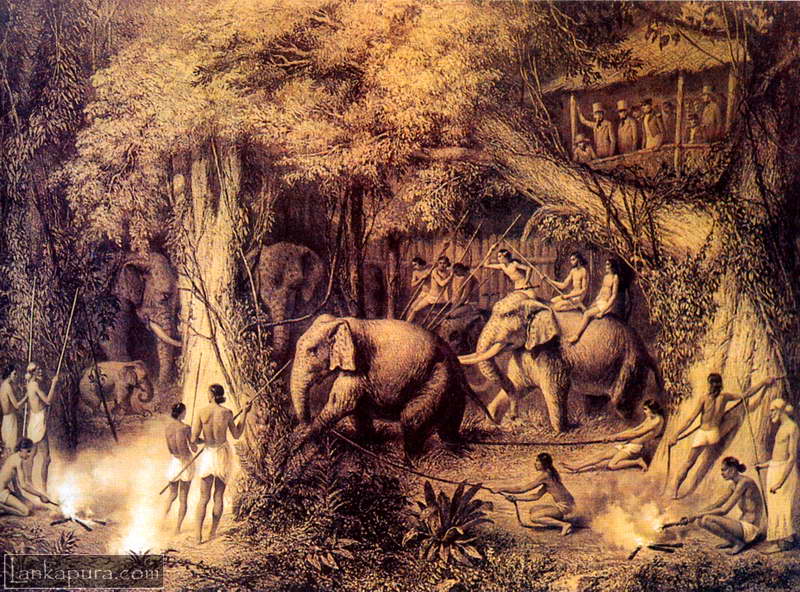

Sri Lanka’s wild elephant population, today confined primarily to the eastern plains and many national parks, had extended to the very highest elevations, and the same was true of the leopard, deer and wild pig. A small proportion of wild elephants were traditionally captured and tamed by skilled Mahoots to become, firstly, temple elephants, indulged and ritualised in return for duties leading processions and carrying deities, and secondly, beasts of work to transport timber.

The traditional system for capturing wild elephants, the kraal (from Dutch), involved large numbers of villagers over many weeks, and took on a ritual performance between animal, human and jungle. There was a further historic tradition of exporting elephants to India. All wild elephants were the property of the King of Kandy and their slaughter or capture without permission was against Kandyan law. Exporting elephants to India and occasionally to South East Asia was thus a high status trade associated with dynastic allegiances and prestige. In 1864, Ferguson’s Ceylon Handbook claims 194 elephants, with a value of Rs 45,920, were exported, while by 1899 this figure had dropped to just 9 elephants but with a total value of Rs17,750[3]. The Sri Lanka elephant had the good fortune to grow only lightweight tusks and only in certain males, which meant that it was not exploited as ruthlessly as the African elephant to provide ivory for the European market.

Apart from those captured and tamed to work on the plantations to move timber and tree stumps, the main attraction of the elephant to the British planter was for sport. Shooting elephant was primarily justified as necessary to protect both the plantation and plantation labourers, with financial rewards for elephants killed, but it also provided much enjoyment for planters isolated on their remote plantations. Popular 19th century sporting literature abounds with tales of the exploits of planters and game hunters such as Sir Samuel Baker, best known as the discoverer of the source of the Nile, who is said to have killed 11 elephants before breakfast one morning and 104 within three days, and complained when the British administration reduced the reward paid per elephant. Major Skinner and Captain Gallwey together recorded killing 700 elephants but were outdone by Major Rogers who killed a record of 1400 elephants in the three years he was stationed as an Assistant Government Agent in the Badulla hills (Storey 1907).

Game hunting in Ceylon attracted the aristocracy of Europe who recorded their exploits in diaries and travelogues. Prince Waldemar of Prussia, in Ceylon in 1844-46 described one incident.

‘I spot an elephant. I take a shot at him and having wounded him we give chase. He slows down and sways and looks around as if thinking … He looks at us with an eye full of reproach and then turns on us. We wait for him motionless and I pull the trigger at the best distance fifteen to twenty paces away …’

Visiting Major Rogers, Prince Waldemar described the scene,

‘his whole house was filled with ivory, for amongst the hosts of slain [1400] more than sixty were tusked elephants. At each door of his verandah stand huge tusks, while in his dining room every corner is adorned with similar trophies …’ (Cave 1904)

Major Rogers’s ignoble tally was curtailed by his early death at 41. He was strike by lightning and killed in the grounds of the Haputale Rest house. His body lies in Nuwara Eliya where a gravestone, also struck by lightning, marks the burial.

The Hungarian Count Emanuel Andrassy, a few years later, wrote extensively of his exploits including the aftermath of a multiple shooting[4].

‘There emerged from a nearby bush a young elephant hardly two feet in height, he stepped up to the dead beast lying next to him which the deserted animal recognized as his mother and sought to suckle from her engorged breast …’

And later describes returning from an early morning sporting outing.

‘Round about stood almost the entire village, mostly women, children and young girls who … looked first at the little [captured] animal and then at us, as we sat on the airy verandah of the thatched house and ate our breakfast, the so-called tiffin, with which the fresh beer went very well …’

Over the course of the 19th and into the early 20th century estimates suggest at least 17,000 elephants were killed (Lorimer and Whatmore 2009) and, despite the growing realisation of the scale of the devastation, the central highlands lost its wild elephant population. In time, the British system of rewarding elephant kills was halted and a sense of conservation and co-existence began to gain ascendency. However, it’s said that the elephant’s memory is long and past cruelties inflicted by planters were revenged by the elephants themselves in popular story-telling, and in the novel ‘Elephant Walk’ by Robert Standish (1948), which became a much-loved Hollywood movie in 1954 starring Elizabeth Taylor, Dana Andrews and Peter Finch. In the story, a wealthy and successful tea planter builds his ‘Big Bungalow’ in the path of an ancient elephant trail, against the grave warnings of local villagers not to anger the elephants. His arrogance and superiority is vindicated in his own lifetime, but it is his son who suffers the retribution and witnesses the bungalow destroyed by the return of the elephants.

While their stories are not so frequently heard, the leopard, deer, wild pig and all bird, reptile and mammal wildlife of the highlands were as decimated as the elephant population by the creation of the plantations. Whether hunted for sport, food (for both planters and labourers) or expulsion from the new landscape, no element of the fauna, from insects to elephants, survived unscathed.

Today

By the early 20th century the plantation landscape we see today was largely in place. The now familiar carpets of tea hugging the contours of the land, interspersed with towering factories, grand plantation owners’ bungalows with their manicured English-style gardens, more modest superintendents’ bungalows and the humble ‘lines’ of labourers quarters. These easily navigated, gentrified landscapes have become a new asset, generating good incomes from tourists and visitors who come to marvel at the scale of the plantations, enjoy the cool climate and experience something of the planter’s life.

The small remnants of original forest that remain now provide precious islands of safe habitat for wildlife. Yet they are too restricted for many species that would naturally roam unimpeded across the expanse of the hills. Now, to reach other safe environments animals must emerge from the forest and cross the plantation spaces where they encounter and interact with the monoculture of tea and human populations. The edge habitats between forest and plantation are hazard zones for animals, plants and humans. Talking with Enoka Kuduvidanage, Professor of Conservation Biology at the Sabaragamuwa University, it is encouraging to learn that there is a community of wildlife and ecology specialists in Sri Lanka who are studying these vulnerable habitats of the highlands and working to support local communities in coexisting with wildlife. With gradual alleviation of poverty within the plantation labour force, increases in rights and access to education, and diversification of crops, life – both animal and human – is becoming more tolerable than it was for past generations – both animal and human.

References

Baker, S.W. (1892) The Rifle and the Hound in Ceylon, New Delhi, 1999, 253 (original published 1892).

Breckenridge, S.N. (2001) The Hills of Paradise, British Enterprise and the story of plantation growth in Sri Lanka, Stamford Lake Publication, Sri Lanka

Cave, H.W. (1904) Golden Tips, a description of Ceylon and its Great Tea Industry. London: Low, Marston and Co.

Knox, R. (1681) An Historical Relation of Ceylon, (London), reprinted 1958 (Colombo)

Lorimer, J. and S. Whatmore (2009) After the ‘king of the beasts’: Samuel baker and the embodied historical geographies of elephant hunting in mid-nineteenth-century Ceylon, Journal of Historical Geography, 35(4), 668-689

Storey, H. (1907) Hunting and Shooting in Ceylon, London: Longmans, Green and Co. Webb, J.L.A. (2002) Tropical Pioneers: human agency and ecological change in te highlands of Sri Lanka 1800-1900, Athens: Ohio University pre

[1] Unclear reference but probable source, Jenkins, R.W. (1886) Ceylon in the fifties and eighties, AM&J Ferguson, Colombo

[2] Probable source, Skinner, T., Fifty Years in Ceylon, London, W.H. Allen & Co., 1891

[3] J. Ferguson (1902) Ceylon Handbook and Directory for 1900-1, Colombo, 651-652, (cited in Webb 2002)